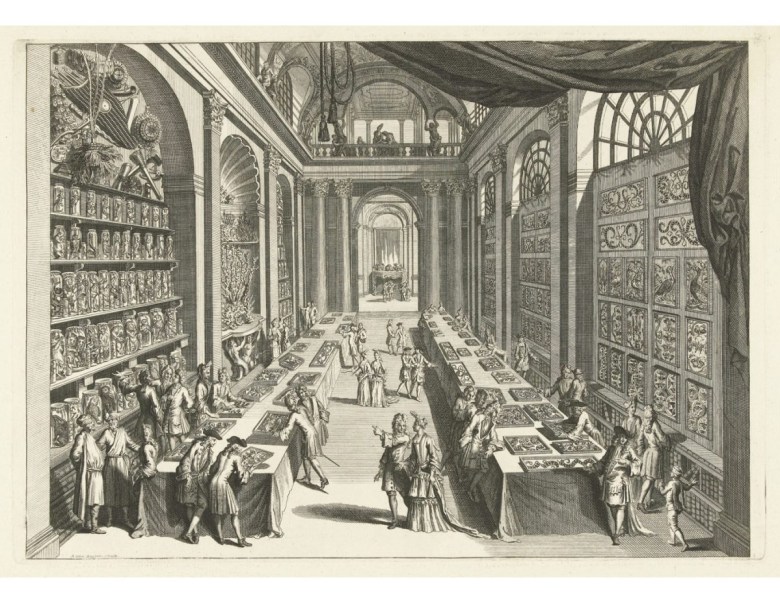

The collection of natural materials has, to some extent, always been a part of human — and even proto-human — culture, but the practice of natural specimen collecting reached a particular zenith in the 16th and 17th centuries, fueled by natural philosophy and the assembly of Wunderkammers by elite households. Though ardor over theory-of-the-world specimen collecting had died down somewhat by the 1800s, herbariums remained an area of interest to many people, including the 19th-century generations of the Timm family, in Sweden.

The Timm Collection is currently housed in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Engelsberg Ironworks in Sweden, and was created by Gabriel Casper Timm and his son Paul August in the 19th century. The father and son assembled their collection in their leisure time, spent collecting plants, insects, minerals, and other natural treasures across Scandinavia, and housing them in elaborate collector’s cabinets.

Collecting Nature: The History of the Herbarium and Natural Specimens (Bokförlaget Stolpe, 2022), by Clive Aslet and Svante Helmbaek Tirén, uses the Timm collection as a starting point for an examination of the history of natural specimen collecting, presenting heavily illustrated page after page of collections through history. Some were assembled by royalty, such as the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II of Bohemia, and many by nobility like Archduke Albert VII of Austria and Henry Somerset, Duke of Beaufort. But specimen collecting, by virtue of being part of the surrounding nature, was a hobby accessible to people from all classes, and especially those who traveled in their work. Wealthy merchants like George Clifford, who assembled a 3,000-specimen herbarium between 1685–1760, had ample opportunity to seek new specimens on their travels, and throughout this period of interest in natural specimen collections, artists found much employment illustrating botanical species and crystal arrangements, and cataloging their patrons’ finds.

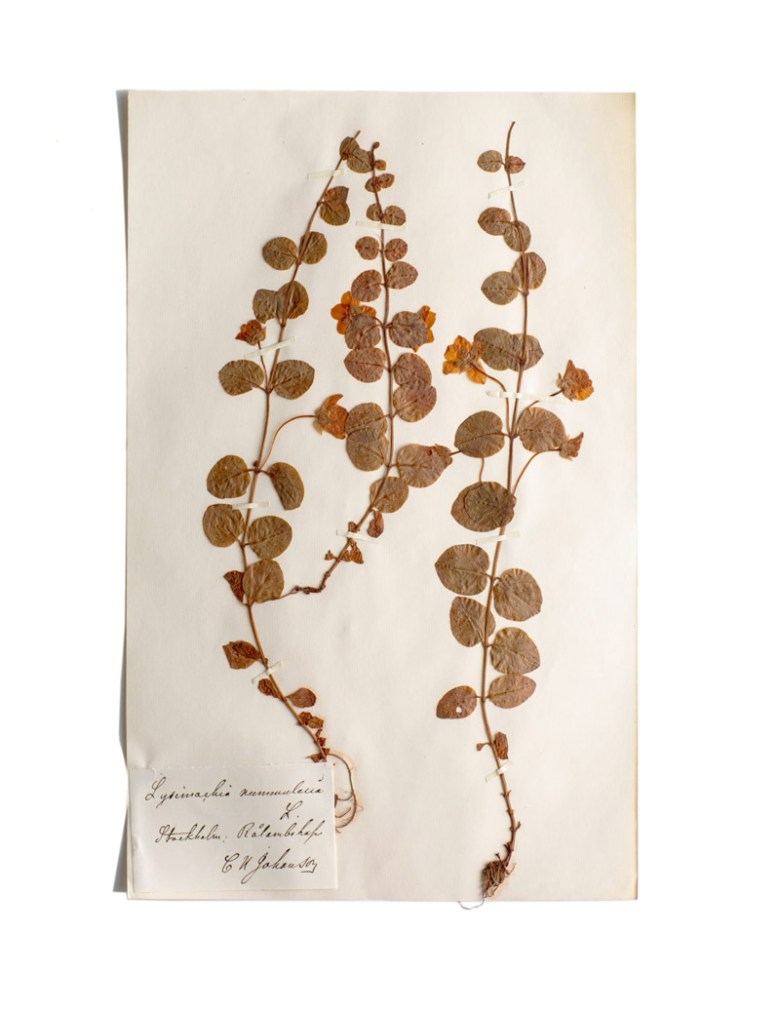

The plants in the Timm collection were assiduously affixed to paper stock, meticulously labeled, and stored in a beautiful wooden cabinet — a common way of housing such collections. Other cabinets carefully cataloged insects, bird eggs, butterflies, minerals, and shells. Though the practice was common, the Timm collection stands out for its excellent preservation over hundreds of years, as many similar collections, even historically famous Wunderkammers, failed to be maintained as the fad waned. Though few letters or other personal materials from the Timm family have been recovered within the ironwork they managed, finding the original cabinet intact is unusual, and offers a great deal in the way of original context for the creation and assembly of the collection. A solid two-thirds of the 200-page book presents color photographs of the Timm collection, in macro and wide views, offering a hands-on sense of work invested there.

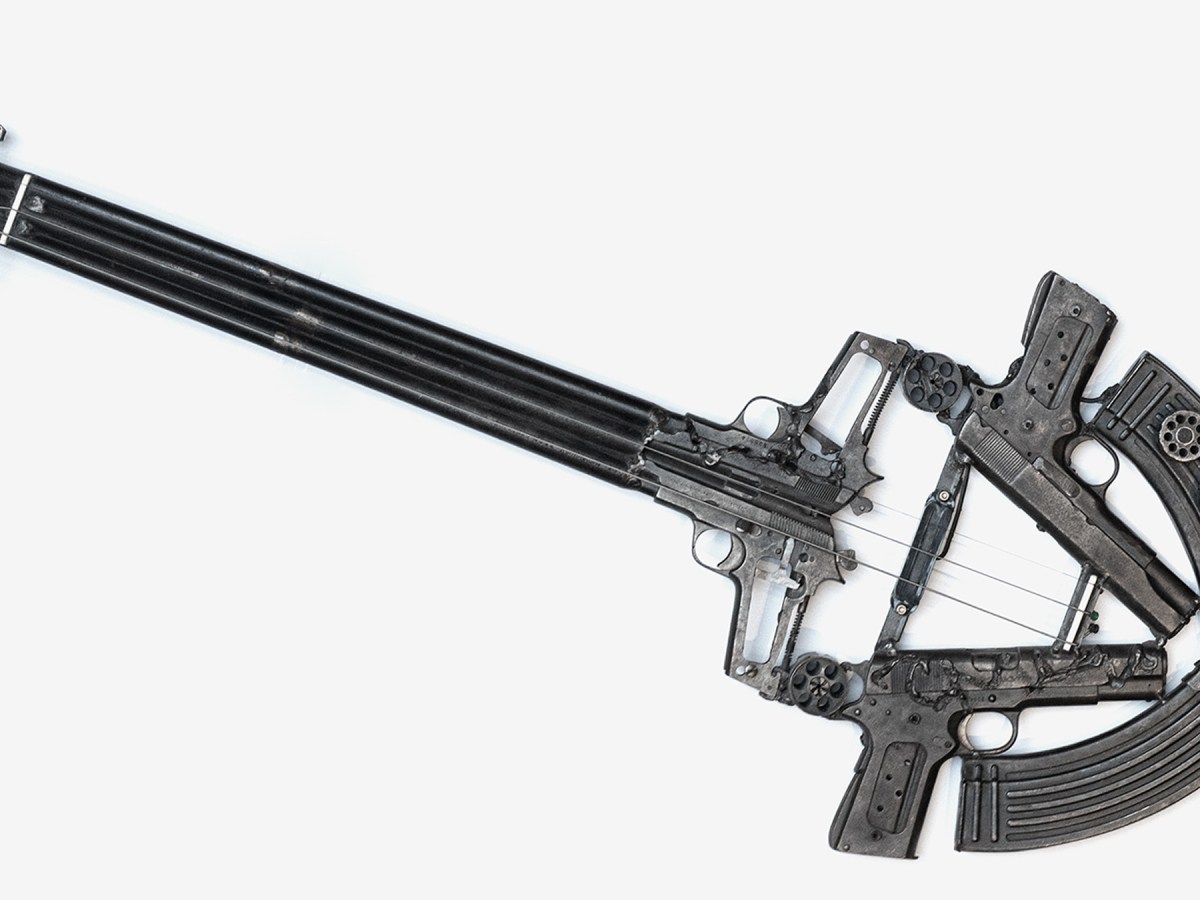

Specimen collecting is a paradoxical practice. Out of a love or fascination with nature, the collector excises little pieces of it, trying to preserve something by killing it. In looking at these collections, one gets the sense of exploration, but also the futile effort to bring order and control to that which already follows its own, organic, sense of order. Collecting Nature adds another layer, making a collection of collections — none of which will ever comprise the whole of what can be, but which offers a satisfying glimpse into the effort to understand what is.