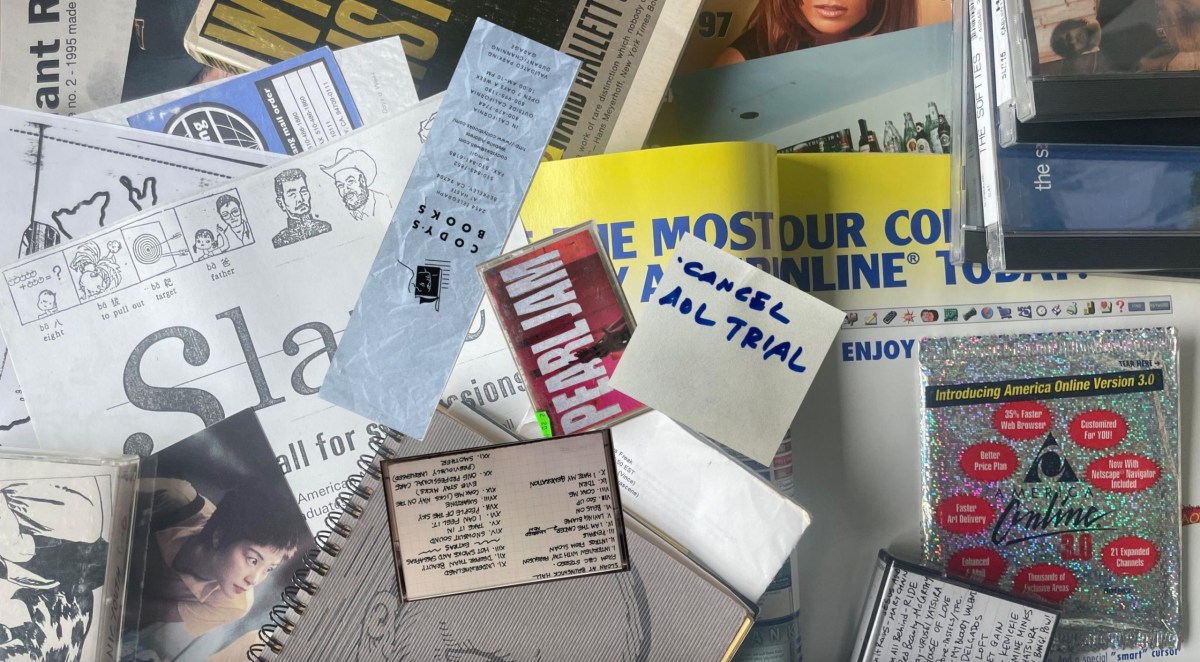

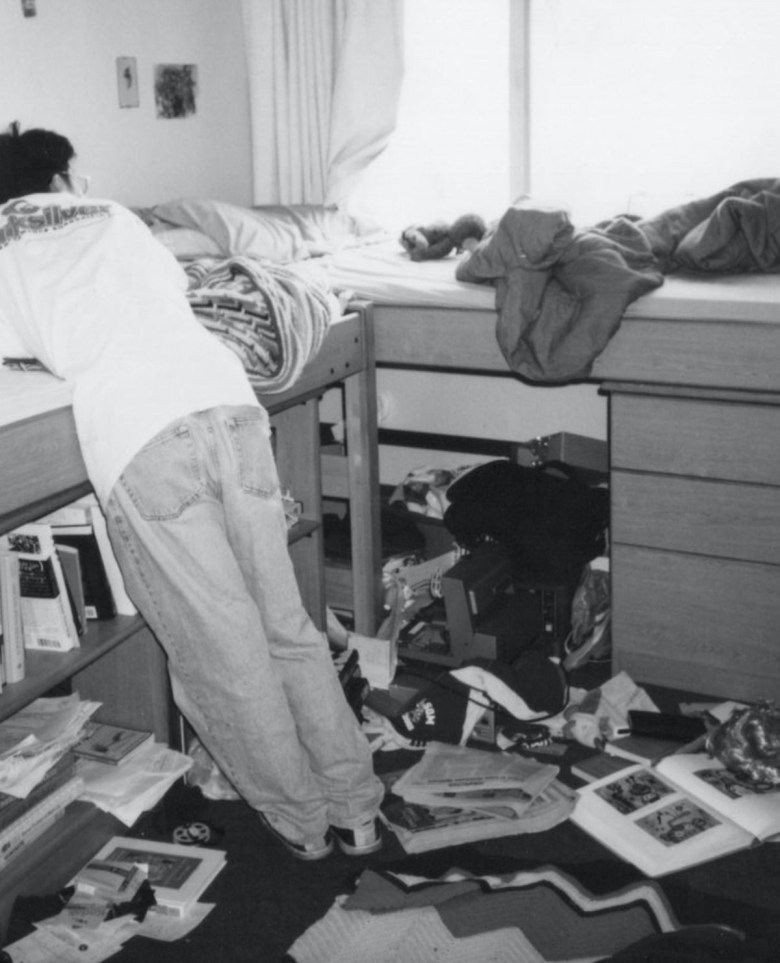

As a teenager residing in a sleepy suburb near San Jose, California, in the 1990s, Hua Hsu first begins creating zines as a way to unlock access to a broader cultural landscape he imagines is waiting for him on the other side of high school graduation. Initially made as an easy way to get free CDs from bands and record labels, the zine quickly coalesces into a manifesto for “cool,” with breathless essays lauding bands like Pavement pasted between takedowns of phenomena that range from braided leather belts to the US police state. In Stay True, the New Yorker staff writer’s recent memoir, Hsu identifies his zine as a testing ground for a future, more authentic self; he writes, “I was convinced that I could rearrange these piles of photocopied images, short essays, and bits of cut-up paper into a version of myself that felt real and true.”

College is a period of transformation during which young people often try out rituals, personalities, and magnanimity in an attempt to see what sticks. It is in the midst of this reinvention during his freshman year at UC Berkeley that Hsu meets Ken Ishida, a charming Japanese-American frat bro with a penchant for the Dave Matthews Band. As a self-styled outsider looking for a sense of belonging in the dusty record bins and bookstores that make up Berkeley’s counterculture scenes, Hsu is dismissive of Ishida, whom he sees as an embodiment of all things mainstream. Friendship, however, is a force impervious to the rigid parameters of coolness, as Hsu soon discovers through the cigarettes, late-night drives, and winding debates the two come to share. As Hsu writes, “some friends complete us, while others complicate us.” The friendship comes to a sudden end when Ishida is murdered in a car jacking off campus during their senior year.

Hsu conveys the enormity of this friendship through a constellation of objects: a VHS tape of Berry Gordy’s The Last Dragon, a Beach Boys CD, a borrowed t-shirt crumpled at the bottom of a hamper. An obsessive collector, the author adheres to the belief that you are your stuff, arguing that “everything you pick up is a potential gateway … that might blossom into an entirely new you.” Within the book he reconstructs these items into a body of proof of Ken’s life, spinning the detritus of a life shared into a tribute to his friend. Hsu references sociologist Marcel Mauss’s “Essay on the Gift,” which posits gift-giving not as an altruistic act, but rather one conducted with the expectation of reciprocity. We leave these items in each other’s lives as a promise that we’ll be back, creating pockets of time. For Hsu, it is within these pockets that relationships happen.

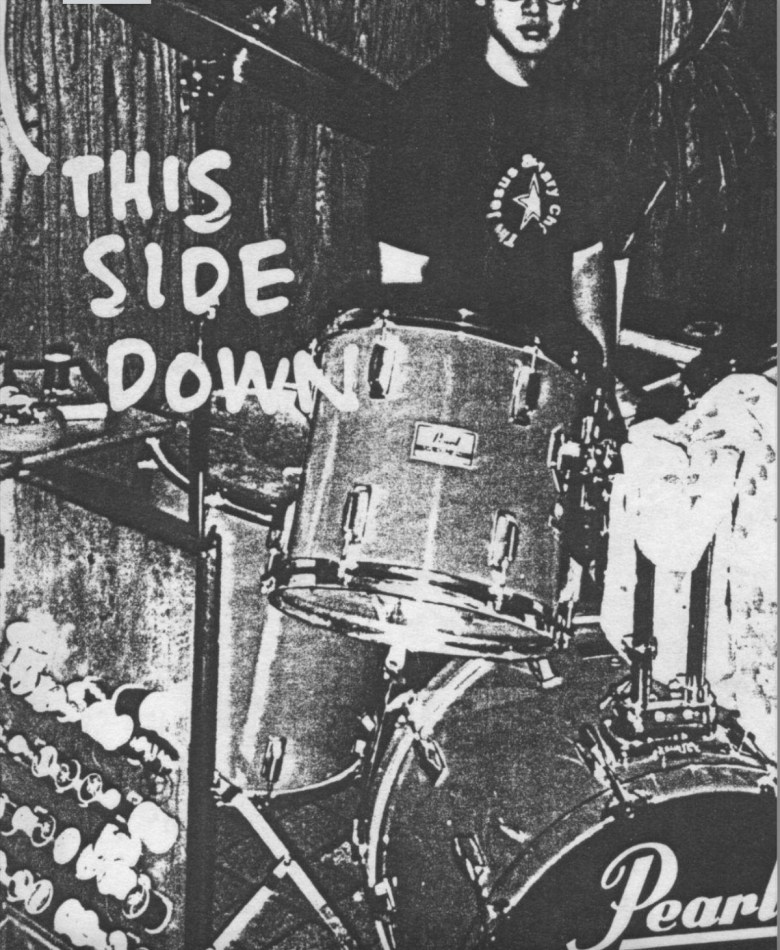

Where the materials he collected had previously served as a gateway into the future, in Stay True they serve as a portal to the past. It is no surprise, then, that Hsu’s memoir is wallpapered with ephemera from his adolescence, from the “faded and distant” surface of the thermal paper faxes through which Hsu and his Hsinchu-based father trade calculus homework help and musings on Kurt Cobain to crumpled flyers advertising underground raves, to the scrawled track list of a mixtape. In his grappling with grief, posterity becomes a primary preoccupation for Hsu, who in the wake of Ken’s death, saves and records every jotted note, scrap, and zine from the period of time they shared together. Resurfaced across the pages of Stay True, Hsu creates an archive of the distinct visual language of the era. Within this rich survey of ’90s ephemera is an homage to the modes of communication that forged community and identity prior to the wide reach of the internet.

Much has been made of the loneliness of Asian-American identity, a catchall term that further alienates the myriad cultural identities it encompasses. In fact, central to Hua and Ishida’s initial differences are the contrasts Hsu finds between his experience “playacting as [an] American,” growing up as a second-generation Taiwanese American in a cultural enclave like Cupertino, and Ishida’s “untroubled” upbringing in a Japanese-American family whose claim to American culture extends back several generations. However, within Stay True is a treatise against loneliness. Hsu eventually finds that they have more in common than he initially thinks — after Ishida is told by a reality television producer for MTV’s The Real World that Asians don’t have the personality for the show’s version of reality he muses, “I am a man without culture.”

Both in this friendship and beyond, we see Hsu searching for belonging. It is within these tender, contradictory, and often messy relationships — with Ishida, Hsu’s first girlfriend, the Mien middle schoolers he mentors, San Quentin prisoners, and others — that Hsu establishes that the construction of one’s identity is not a solitary endeavor but rather one rooted in deep and intentional connection with those around us.

In Stay True, Hsu turns to Jacques Derrida’s meditations on the transience of friendship, citing the philosopher’s belief that “To love friendship, one must love the future.” As Hsu writes from the present, his careful documentation of the world he shared with Ken Ishida, as well as the threads of Ken’s influence on his own life, are a testament to the inverse — that to love the future, to believe that it is something good and hopeful and worth building toward, is impossible without a love of friendship.

Stay True: A Memoir by Hua Hsu (2022) is published by Doubleday Books and is available online and in bookstores.