Every year since I first had the pleasure of studying art history at university, I have longed for a sourcebook “detailing” art from India.

I am sometimes quite annoyed with publications with “global” in their titles that continue to reduce tones of art historical material from South Asian countries like India and Pakistan into a few pages, while chapters on Eurocentric art seem never-ending. Thus, every semester, I continue to hunt for the best possible written sources for my undergraduate students who are keen to learn — critically and in depth — about the many distinct aspects of art in South Asia. I am highly relieved to report that now a title compiling remarkable research on the subject is finally available to academics, students, and general readers.

20th Century Indian Art (Thames & Hudson, 2022) brings over 600 pages worth of generously illustrated essays on modern, post-independence, and contemporary Indian art. The volume is coedited by historian of art and culture Partha Mitter, and art historians Parul Dave Mukherji and Rakhee Balaram. While the volume is not all-encompassing or encyclopedic, the content is plenty and is divided into four major parts. The first three sections chronologically scrutinize Indian art, while the last briefly introduces art history in the nation-states of Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Bangladesh, closing with artist and critic interviews.

Rather than the coeditors penning every chapter in the book, the publication connects several articles and essays by many writers. Part I brings notice to challenges faced by Indian artists while reclaiming their national identity during the era of colonial modernity in India. Saloni Mathur’s “Retake of Amrita Sher-Gil’s Self Portrait as a Tahitian” explores how Sher-Gil, a Hungarian-born Indian artist of tremendous importance, gave rise to the early 20th-century Indian avant-garde by invoking a Gauguinesque female nude and elements of Japonisme in earthly palettes in her self-portrait. Amongst other writings, Naman P. Ahuja writes about the anti-imperialist land- and history-driven Indian Arts and Crafts movement while Sanjoy Mallik offers social context for the works of the Calcutta Group during the devastating Bengal famine of the 1940s.

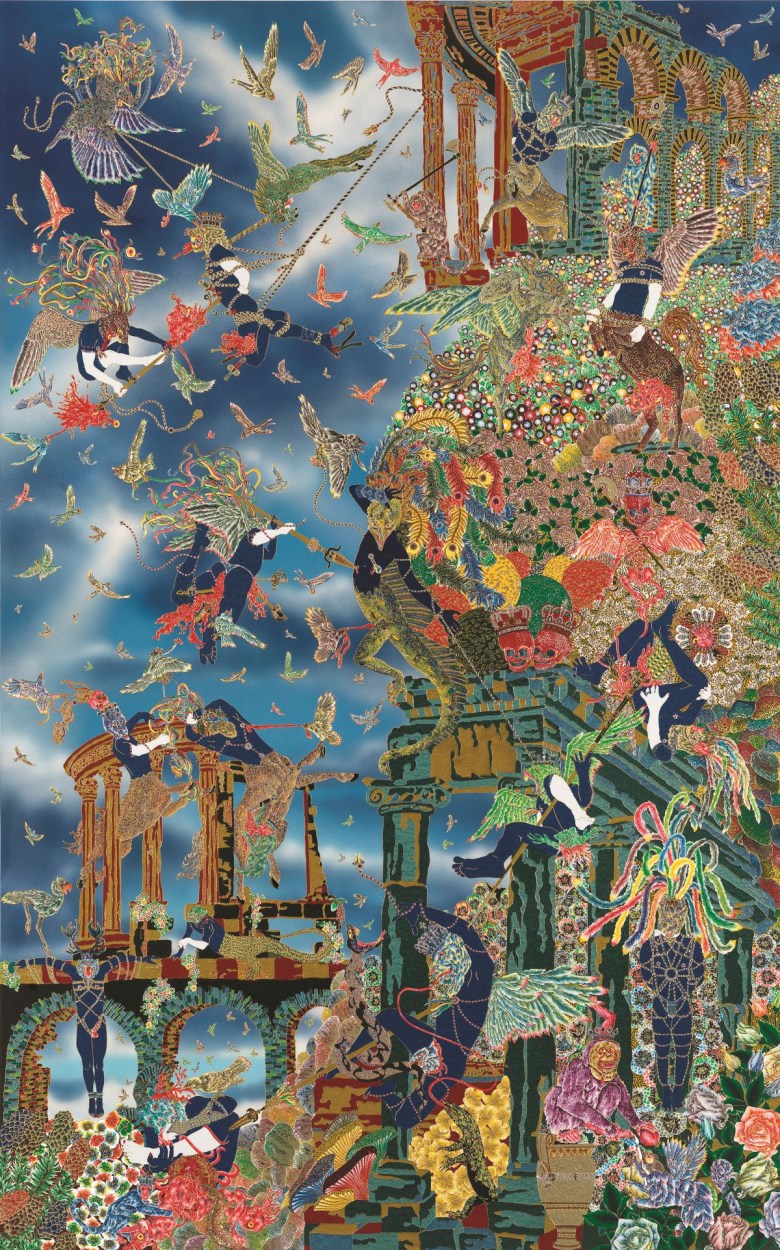

Post-independence, Indian art decentralized into an idiosyncratic interpretation of “what it means to be modern,” especially in the aftermath of colonialism. The “modern” in Indian art is audacious and self-aware, figurative and abstract, political and personal, ornamental and minimal, regional and beyond. Writers expand these narratives in the second part of the book, addressing modernity through regional activism, including the ornamental aesthetics in Andhra Pradesh, the complicated history of museums, post-colonial modern art groups such as the Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG), monumental sculpture, and writings of modern critics.

Within India, no modern art style or movement was the same or derivative of the West, as commonly misunderstood. Explaining that many women artists and local villages constituted an original modern style in Madras, Ashrafi S. Bhagat writes, “The emergence of Modernism in South India was distinct from the West as well as New Delhi.” This section also covers art forms such as photography. In her essay “Framed Borders: Photography in India After Independence,” Rahaab Allana considers photography instrumental for national celebration; one that set out “to document India’s historic transition into political sovereignty and nationhood.”

Here, readers will find further contextualized underpinnings of post-colonial Indian art. In “The Delhi Silpi Chakra: Art and Politics after the Radcliffe Line,” Atreyee Gupta demystifies constellations between Pakistani and Indian artists who came to be associated with the Mayo School of Art (now the National College of Arts in Lahore), established in 1857 by the British, and the Lahore School of Fine Art, inaugurated by Indian artist Bhabesh Chandra Sanyal, who also cofounded the collective Silpi Chakra.

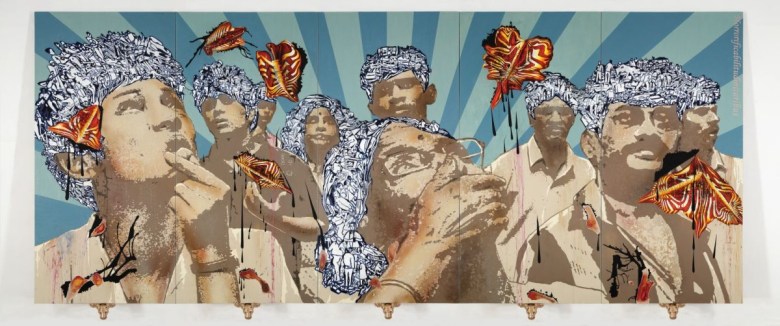

I am especially delighted with this volume because, as an academic and historian of South Asian art, the title introduces vital perspectives on the subject to readers. For instance, in “The Making of The Baroda School: When People Become Public,” Parul Dave Mukherji considers the alternatives of internationalism, politics, and photorealism in the art from Baroda School, where the urgency in the comeback of the figure transpired as a polemical response to abstraction in modern Indian art. Further, to supplement research on artists and movements, essays by Sonal Khullar and Kavita Singh expand on the role of criticism and academic print for modern Indian art, and the role of museums and displays in India through specific case studies, respectively.

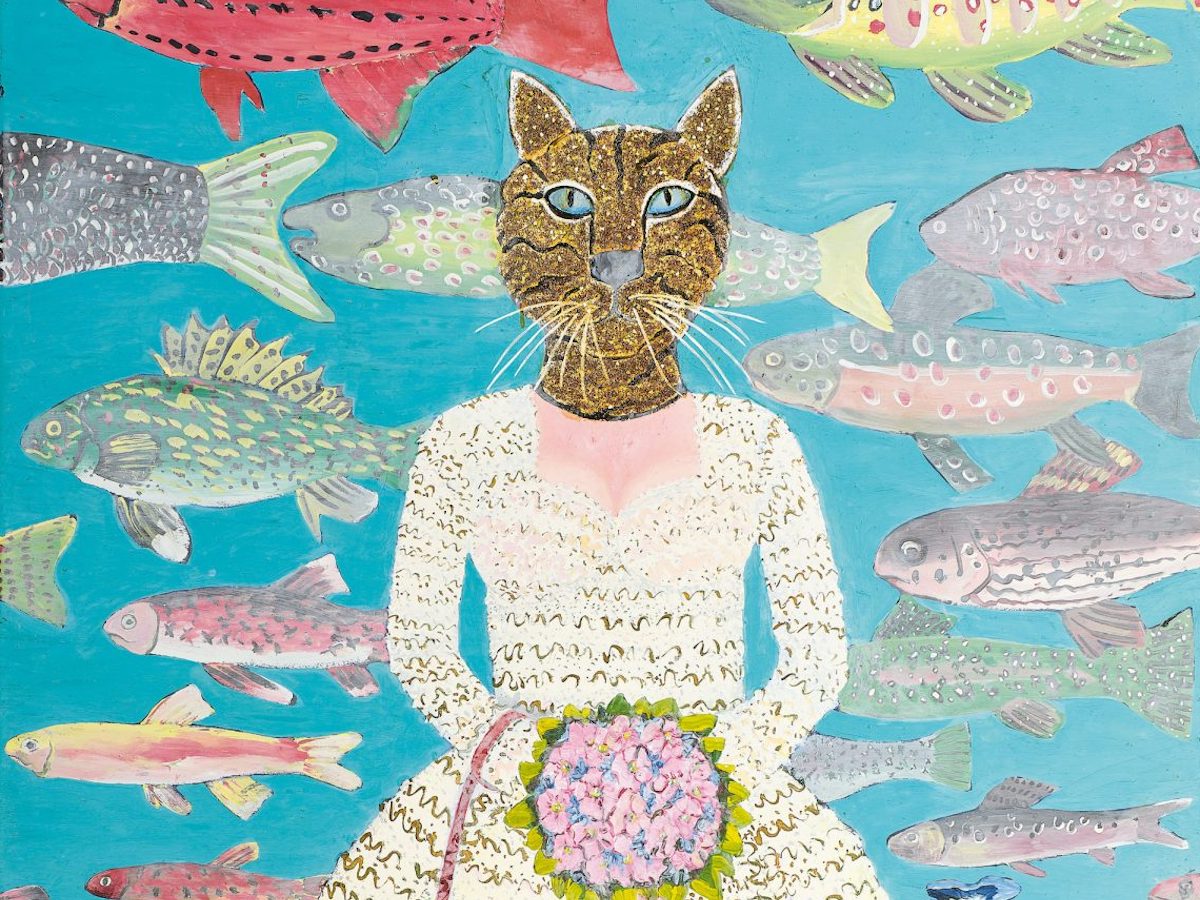

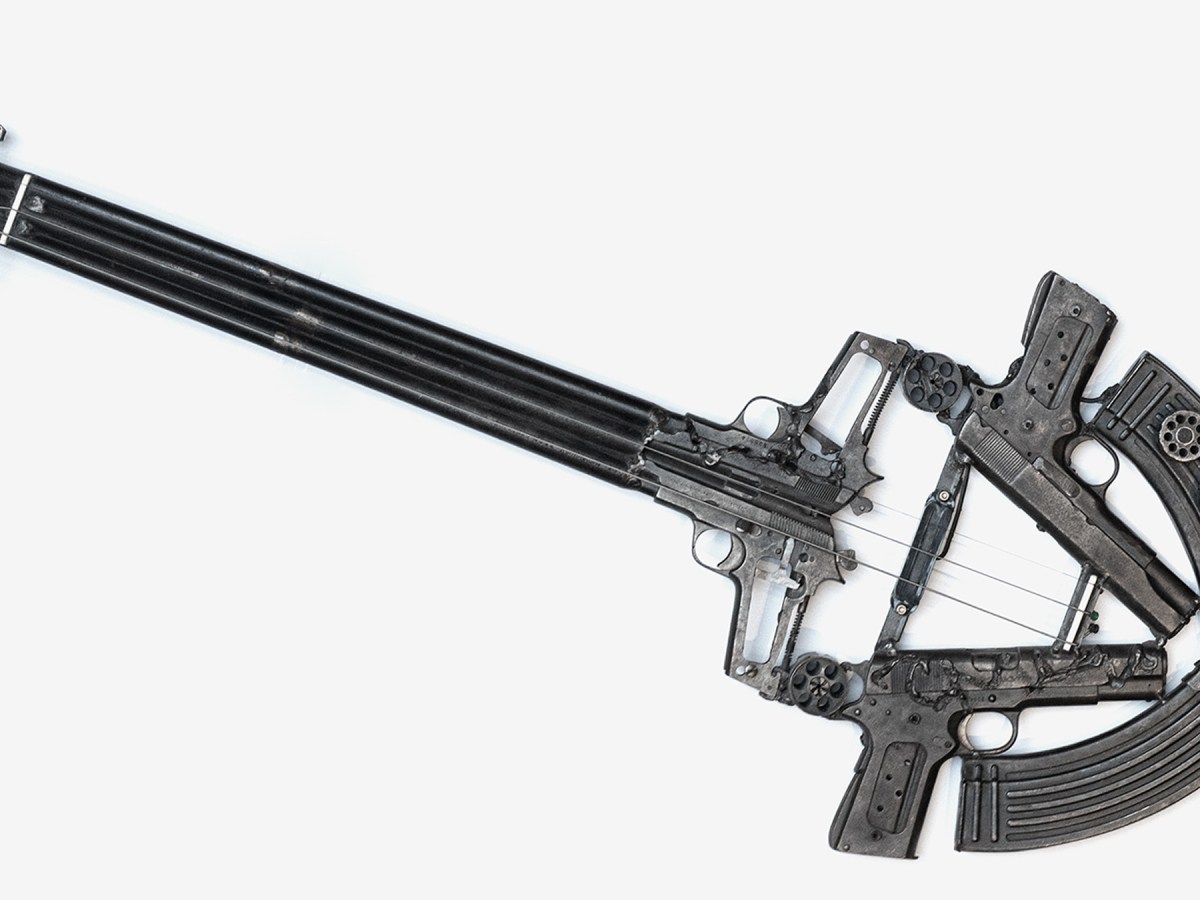

Consequences of globalization, technological breakthroughs, conflict, contemporary society, and exhibitions have significantly shaped Indian art and its diaspora at the turn of the 20th century. In Part III of the book, many writers bring Indian art into a robust dialogue with trends from neighboring countries such as miniature painting from Pakistan, the state of the Indian art market, works of Indian artists being exhibited in the West, films, and international biennials. Additionally, Gayatri Sinha analyzes Indian women artists whose works were being impacted by feminist discourses in “Revisitations: Women Artists of India Since the 1990s.”

The book concludes with in-depth and nuanced interviews conducted with renowned critics and artists including Tapati Guha-Thakurta, Anita Dube, Geeta Kapur, Iftikhar Dadi, K. G. Subramanyan, Jogen Chowdhury, Krishen Khanna, R. Nandakumar, Jitish Kallat, and Raqs Media Collective.

20th Century Indian Art illustrates styles of art and craft in India that are complex and deeply enmeshed with geopolitics, identity, nationhood, post-colonial sensibilities, and creative subjectivities. At every page, readers enjoy pleasant visuals and sound research in this highly instructive sourcebook, urging us to broaden our minds as we critically approach these unique strands of Indian art history.

20th Century Indian Art: Modern, Post-Independence, Contemporary (2022) by Partha Mitter, Parul Dave Mukherji, and Rakhee Balaram is published by Thames & Hudson and is available online and at independent booksellers.