Editor’s Note: This article is the fourth in a four-part series about artists and art movements in Los Angeles and it was made possible by a grant provided by the Sam Francis Foundation.

LOS ANGELES — In a year of massive layoffs, outcries against systemic racism, and our first official global pandemic, it is little wonder that some may be looking beyond the material world and seeking spiritual sustenance, even in the usually secular art world. Increasing global economic and political uncertainty — and not to mention the ongoing reality of climate change, which remains impervious to human calamity — has given new meaning and resonance to one of fire-and-brimstone preachers’ favorite topics: the apocalypse. If indeed the end is not near, it certainly seems near.

As per usual, art reflects the context from which it emerges. While there had already been a growing trend toward exhibitions exploring spirituality in art (see: Hilma af Klint at the Guggenheim, which became the museum’s most-visited exhibition ever), discussions around art as a spiritual practice appear to be ever more salient and pertinent, particularly among certain Angeleno artists.

“A lot of people have been turning to art, needing space to process,” said the artist Edgar Fabián Frías over a phone call. “We’re all collectively moving through a lot of trauma together.”

Frías, a native Angeleno, incorporates spiritual rituals adopted from their indigenous Wixárika heritage into their work, along with an array of other mindfulness practices and is, in addition to an artist, a licensed psychotherapist. While normally based in Los Angeles, Frías is currently a visual arts fellow at the Tulsa Artist Fellowship in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a city recently ruled Native American territory in a landmark Supreme Court decision. During April and May of this year, Frías hosted weekly livestream pieces on Instagram for the Vincent Price Art Museum in Los Angeles called Meditation Mondays. The series aimed to “set the tone for the week supporting wellbeing, healing, mindfulness, and gratitude” and introduced viewers to a variety of spiritual and therapeutic practices including, of course, meditation, delivered in their benevolent, calming voice. Said Frías of the project, “there’s so much grief in the air right now. Spirituality and coming together are ways we can keep sustaining each other as we move through this time.”

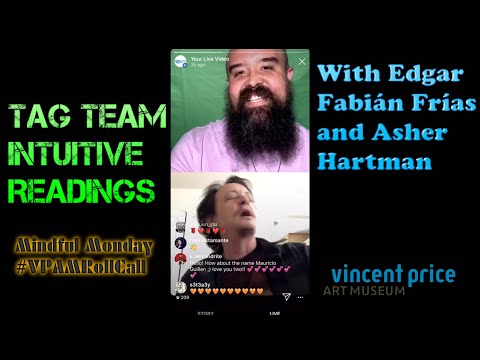

Much of Frías’s work revolves around community empowerment and collaboration. For many of the Meditation Mondays sessions, for instance, they invited artists and friends as co-presenters. Artist Asher Hartman accompanied Frías on one livestream in which Hartman performed intuitive readings of viewers’ submitted names, telling one viewer that inhabiting her name made him feel like he was in “a bucket seat above the world.” Spoken passionately with his head thrown back and arms outstretched, the readings are charming and captivating. Frías followed up the readings by drawing and interpreting tarot on the same name. In another, Frías was joined by artists Ofelia Esparza and Rosanna Esparza Ahrens on the topic of creating sacred spaces, with the intention that viewers could learn about the process, its potential in self-care practice, and create their own.

For several years now, the Los Angeles-based artist Hayley Barker, who lives and works in Crestview, has taken a more introspective approach to the intersection of art and spirituality. Her paintings, typically oil on linen and a colorist’s dream, carry an intense emotional weight that gives depth to the subjugation that their female subjects experience. For instance, in “Astrology” (2020), exhibited in February at the BozoMag booth of Art Los Angeles Contemporary’s 2020 fair, Barker depicts the German-Jewish painter Charlotte Salomon, who was murdered by the Nazis, using Salomon’s own self-portrait as the basis of the work. In the painting, Salomon confronts the viewer with her bright eyes and angular bone structure, with the word “Astrology” simply painted onto the surface, as though Barker were communicating with Salomon through the stars. Says Barker of the piece, “Looking at her portrait now, (and the self-portraits of other painters) I suspect that we somehow wear our traumas all over our faces. And that includes traumas that have yet to come.” More recently, in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, Barker painted “Still Angry” (2020), in which an anonymous woman stares directly at the viewer, her fair skin marred with a sickly tinge of green, yellow, and blue. She appears despondent yet determined. “Anger is a spiritual project,” Barker said over email.

Like Barker and Frías, artist Julie Weitz has been making space for emotional response during moments of political upheaval — and she has invented a character to do so. Weitz, who has lived in Los Angeles for seven years, created the long-running project MY GOLEM (2017–present) to serve as a vessel for exploring calls for social justice and the various feelings and traumas that these injustices produce, all through the lens of a golem character whom Weitz says “revitalizes the golem mythology as an empowerment fantasy.” In a video posted on Instagram on July 6, “GOLEM MEDITATION” (2020), Weitz conducted a Zoom meeting with the golem character, leading it through a meditation with Hebrew letters until Golem, overcome with emotion, finally breaks down.

Golems are significant to Jewish mythology and generally mean something akin to an unfinished human or a raw form, though interpretation of both the mythological creature itself and its meaning are highly mutable. They tend to be depicted as dumb and inherently obedient, though sometimes they are portrayed as rebelling from their master-like creators. Following this vein, Weitz’s golem regularly takes stances on social justice issues, such as in MY GOLEM PROTESTS (2019–2020). The performances, and the photos documenting them, depict Weitz as the golem character protesting against ICE detention centers. The Golem character, dressed in a lavish costume consisting of a white leotard, tights and full-face makeup, holds up signs that say “NEVER AGAIN MEANS FREE THEM ALL” and “CLOSE THE CAMPS,” drawing parallels between the United States’s current treatment of immigrants and the Holocaust.

Artist and activist Patrisse Cullors, perhaps best known as co-founder of Black Lives Matter, has consistently referenced spirituality in her performance work as both a coping mechanism and a call to action. In Prayer to the Iyami, performed at the Broad before the shutdowns earlier this year, Cullors uses her older brother’s clothes to build a 20-pound tapestry of wings, which she then wore. Each pound of its weight symbolizes the 20 years she has spent attempting to protect her brother from imprisonment and police brutality. Cullors says on her website that she thinks of the piece “as a love letter to Los Angeles and, most importantly, a loving prayer for her brother Monte,” affirming art-making as inextricably linked to the fight for social justice and spiritual solace as an antidote to the exhaustion it can produce.

On June 13, Cullors performed “A Prayer for the Runner” over Zoom as part of a celebration of Pride month and the Stonewall Uprising of 1969 at the Fowler Museum. In her performance (available to watch in full above), Cullors enacts a spiritual ritual for Ahmaud Arbery, who was fatally shot by white vigilantes near Brunswick, Georgia while on a run. On the right side of the split-screen video, Cullors physically performs the ritual, lighting candles on an altar below another set of wings, while on the left, the words of the prayer are depicted in subtitles, appearing and disappearing as Cullors moves through them. Cullors orates clearly and in an even tempo, saying “you were running for respite” to the spiritual entities of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd.

Throughout these practices, Angeleno artists are processing their emotional responses, both political and personal, to the incredible upheavals of this year and beyond. In the context of stay-at-home orders and shutdowns that ebb and flow on a seemingly endless basis, it is perhaps unsurprising that the artworks depict both the longing for community, as with Frías’s Meditation Mondays, and the need for thoughtful introspection, like with Barker’s “Still Angry.” Continuing on a trend that was already brewing, the stark events of 2020 have served to move the spiritual impetus in art forward, albeit in an often more direct, politically affected way.

I’d like to highlight The Secret City as an organization that offers artistic spiritual relief during the pandemic. Chris Wells has a daily live FB program, “Daily Artistic Inspiration for Troubled Times” 9am PT/12noon. https://thesecretcity.org/